Loveland council OKs $155M tax-increment plan for Centerra South

LOVELAND — On a 6-2 vote at 12:45 a.m. Wednesday, the Loveland City Council approved a tax-increment revenue-sharing agreement between the city and the Loveland Urban Renewal Authority to spur development of McWhinney Real Estate Services’ proposed Centerra South project.

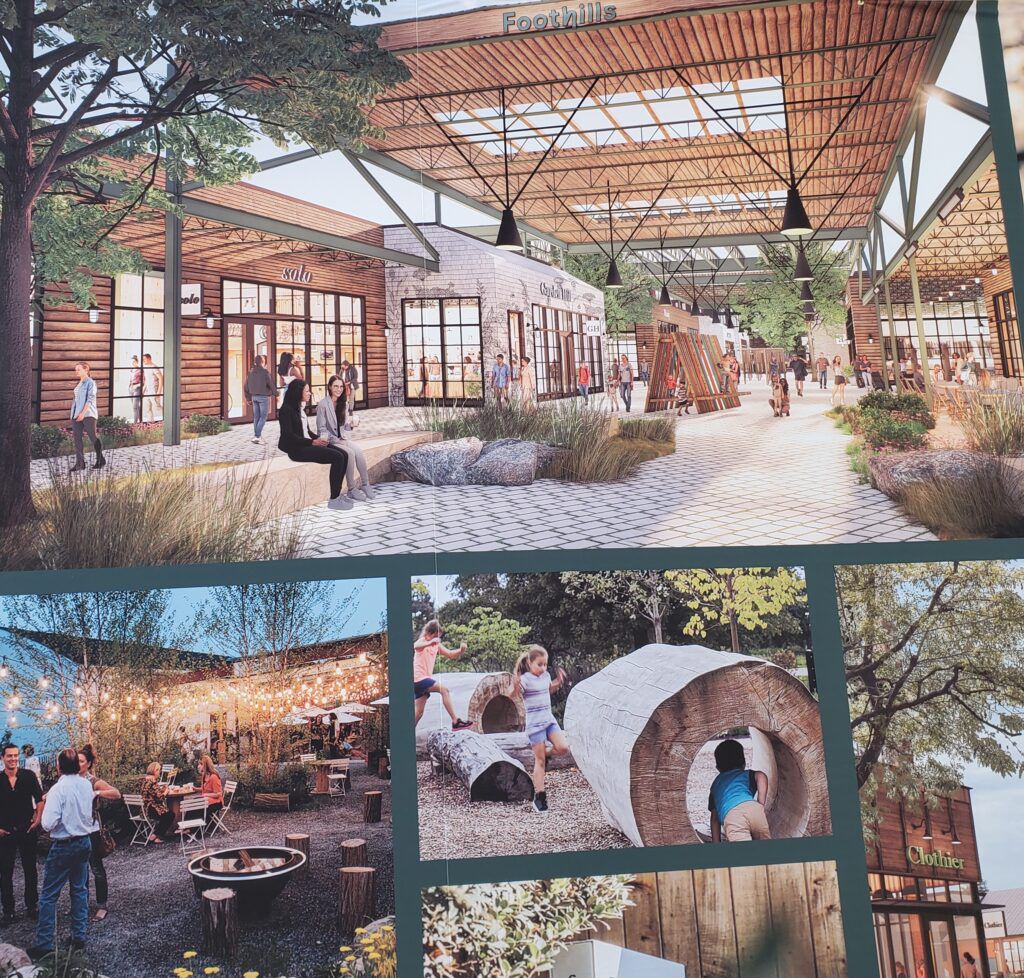

Centerra South, a mixed-use commercial and residential project to be located south of U.S. Highway 34 and west of Interstate 25, is anticipated to cost approximately $1 billion to construct, according to city documents, and would require approximately $155 million in public infrastructure investment. To accomplish that goal, the land area designated for the project would need to be removed from the US34/Crossroads Corridor Urban Renewal Plan and placed in a new Urban Renewal Plan, but that required completion of negotiations related to the tax-increment revenue sharing agreements and the proposed Centerra South Master Financing Intergovernmental agreement.

The council voted 7-1 to extend until May 2 the public-notice period for the vote on changes to the original Centerra urban renewal plan. Mayor Jacki Marsh dissented because she contended that the vote was illegal because an extension would exceed the required period for public notice.

Less contentious was the council’s earlier unanimous vote Tuesday night to dissolve the Downtown Loveland Urban Renewal Authority because of its redundancy with the public-financing work of the Downtown Development Authority. The $1.8 million left in the downtown portion of LURA’s funds will be used to pay off its remaining obligations.

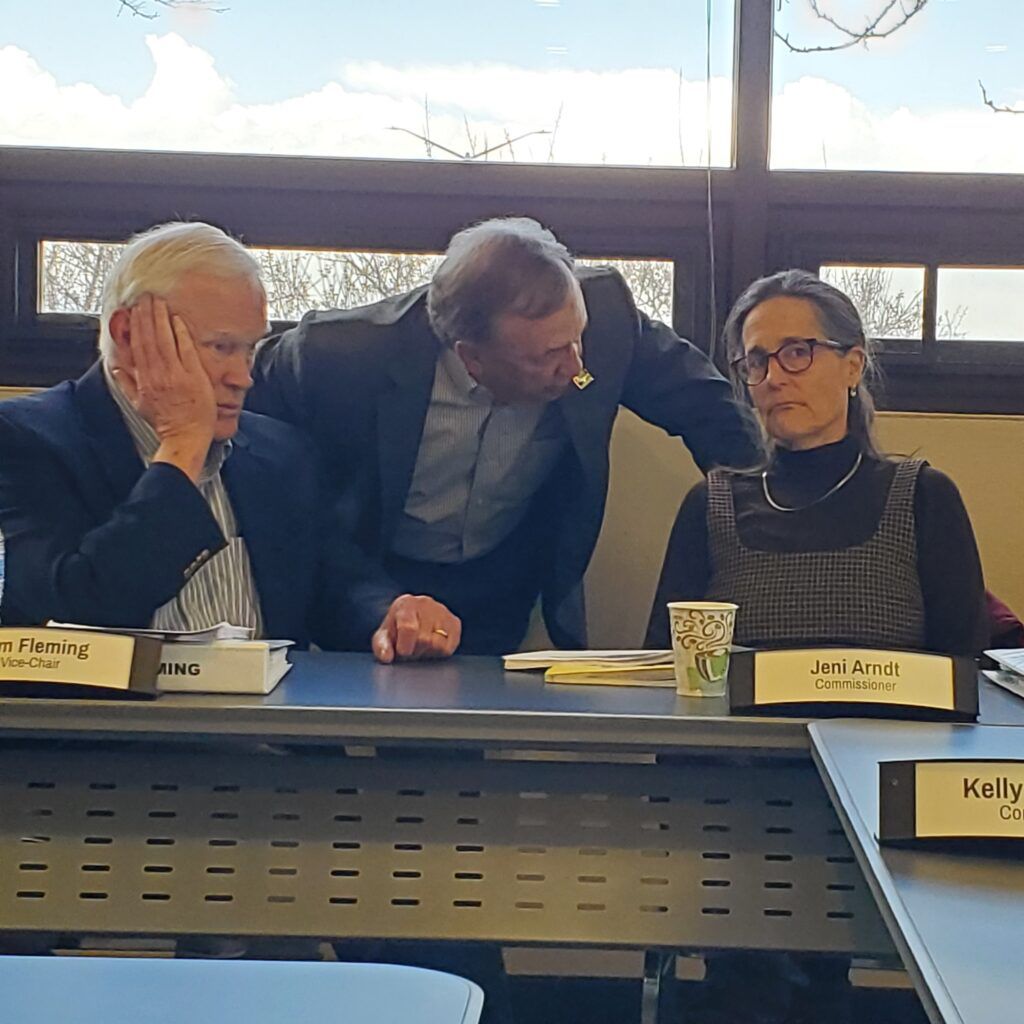

To approve the Centerra South tax-increment revenue-sharing agreement, Colorado law requires LURA to negotiate with tax collecting entities that levy a mill within the proposed Urban Renewal Plan Area, prompting LURA, city staff and members of the Loveland City Attorney’s Office to conduct negotiations with the city, Thompson School District, the Northern Colorado Water Conservancy District, Larimer County and the Thompson Valley Health Services District.

The city council was told at its last regular meeting April 4 that the total cost of developing Centerra South would be $1.049 billion, with half paid by construction debt borne by McWhinney, 35% from construction equity paid by the developer and and $155 million, or 15%, paid by public investment. Forty percent of that public money would come from tax-increment financing through LURA, 49% from new metro districts created within the development, and 11% through a 1.25% tax on retail sales made in that area.

Beginning consideration of the tax-increment plan itself, Deputy City Attorney Vince Junglas, speaking in his role as principal negotiator for LURA over the past four months, offered a forceful presentation touting the benefits of the project with data he called “challenging to ignore.”

“The South Centerra project as it is proposed will haul in approximately $272 million over the next 25 years for all of our tax-collecting partners,” Junglas said. “Not a single tax-collecting entity will pay more in services than they will receive in excess revenue consistent with conservative estimations and projections with what is on the table. If the urban renewal plan for Centerra South is not adopted, the tax-collecting entities will receive the status quo, which amounts to approximately $118,000 over 25 years for all the entities, and that’s assuming no development were to occur.”

McWhinney, he said, “will be taking on some measure of risk in this proposed transaction that requires a long-term commitment to Loveland. The McWhinney organization will pony up $367 million of their own money, which constitutes a little more than a third of the project.”

He said the city of Loveland “has proposed to share 100% of the property tax increment with LURA, but the remaining sales tax, lodging tax and fees … will provide the city with approximately $1.5 million in present dollars annually for the next 25 years. There is compelling evidence that the city and all the tax-collecting partners will capture unanticipated revenues that may be reinvested into the community in a manner seen fit by the tax-collecting entities and their constituents, the people of northern Colorado.”

Junglas blasted state Senate Bill 273, proposed by Sen. Janice Marchman, D-Loveland, which seeks to redefine how agricultural land can qualify for urban-renewal designation, as legislation he said “appears to be for the sole purpose of crushing the proposed Centerra South development, including approximately 1,255 attainable housing units. Nobody could have guessed four months ago that the power of the state, through what I would call the ‘No Whole Foods bill,’ would be used to kill a single proposed transaction, let alone one that is conservatively estimated to substantially benefit each tax-collecting entity.”

He also criticized Larimer County’s decision not to participate in the agreement.

“The county has an opportunity right now to seize whatever may be left of local control through this proposal by coming back to the table, and thereby rejecting the state’s intentional attempt to kill a beneficial project on what is tantamount to a technicality,” Junglas said. “The county has a choice to consent and seize an opportunity to invest $57 million of unanticipated revenue over 25 years without adversely affecting Larimer County’s cost of service. Or, the county may desire to watch more tumbleweeds fly across U.S. 34, hopefully avoiding one of the 18 million cars traveling across Centerra South’s northern border each year.”

To cure the blight designation required for an urban-renewal project, Junglas said, “a developer could build a few roads, some pipes, throw in some power, strip malls, some multi-family housing and a gas station. Blight, and thus the barriers to development, are still remediated for a fraction of the total cost of Centerra South as proposed. This hypothetical development is a bronze remediation project, a project that does not deliver anything unique, dynamic or desirable to the city’s entryway, a project that is likely not worthy of public investment for Loveland but a project that crosses the finish line under the urban-renewal law.

“What does a gold project look like? Centerra South, that’s what it looks like.”

Some of Junglas’ rhetoric — “a project of significant magnitude with state-of-the-art world-class structures,” “an attractive pillar of Loveland’s entryway” and “a home-run deal” for the Thompson school district — rankled Marsh, who asked the city attorney “how, in that capacity, giving legal advice to the city and city council, is that propaganda that you just read?”

However, Mayor Pro Tem Don Overcash objected to what he called the mayor’s “Improper use of language” and Junglas responded that, “if I’m acting in the capacity of a negotiator, I owe a duty to LURA to seek a deal that is most advantageous for that entity.”

Marsh maintained her opposition to the revenue-sharing plan.

“I have not heard one person say they’re against the development,” the mayor said, but added that “we would like a developer whose property value has greatly been enhanced by public dollars to pay their own way.”

She was joined by Councilor John Mallo, who said “I don’t think it’s urban, and I don’t think it’s blighted. I’m not anti-development. I’ve supported all kinds of development in this city and I’ll continue to. I just don’t think this is the right thing. I like this development; I don’t like the financing part of it.”

Pointing to the expansive list of projects on the developer’s website, Mallo said, “I don’t think McWhinney needs us.”

However, Councilor John Fogle responded that “the McWhinneys don’t need us, but we need the McWhinneys.”

He pointed to Walmart and Costco, which built in Timnath “because Fort Collins simply screwed up,” and to the 2534 development that ended up in Johnstown — “Scheels and 40 other stores across the street from us that suck the sales tax right out of Loveland. We get all the traffic and all the expense and none of the income.”

McWhinney had been in negotiation with another major outdoor retailer, but “we as a city farted around for so long that Bass Pro Shops went away,” Fogle said.

“The cities around you grab the development and off they go with them,” he said. “We have to decide as a community whether we want to grow or whether we want to die.”

Source: BizWest