Hospitals’ next hurdles: Worker shortages, inflation, Medicare gaps

The COVID-19 health care crisis tested hospital staffs’ resourcefulness and stamina in the Boulder Valley, Northern Colorado and across the nation.

Their next crisis, however, is proving very different.

“We were excited to come out of the pandemic and kind of elated when numbers started to decline, and we were seeing fewer and fewer patients becoming critically ill with COVID-19,” said Kevin Unger, president and CEO of UCHealth’s Northern Colorado region, which includes Greeley Hospital, Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins and Medical Center of the Rockies in Loveland. “But then we didn’t realize just how challenging health care was going to become from that point forward.”

Now, “we’re facing a significant math problem. It’s no longer a health problem,” said Dr. Robert Vissers, president and CEO of Boulder Community Health.

When Medicare and private insurance reimbursements don’t cover the rising prices of labor and technology, he said, it creates “a huge gap — too large for any system to recover from in a given year.”

Other hospital executives in the region find the math alarming as well.

“When you have costs going up 8% a year at best and reimbursement going up only 4%, you can’t run a business like that forever,” said Lonnie Cramer, president of UCHealth’s Broomfield Hospital and Longs Peak Hospital in Longmont. “That’s an equation that will need to be resolved.”

Added Unger, “It’s not a great business model right now.”

Worker shortages, rising costs and low Medicare reimbursements, coupled with the restraints imposed by state and federal legislation, are prompting hospital executives to say the coming years probably will be more disruptive than COVID.

“I’m one of those voices,” Vissers said.

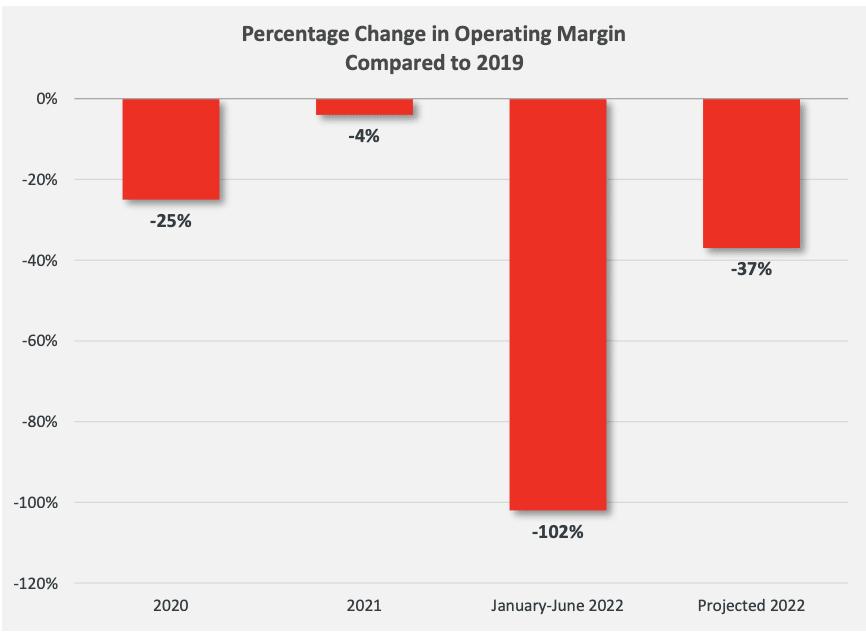

In its fall 2022 report on the state of hospital finances, Fort Collins-based consultant company Kaufman Hall said “projected margins are on track to make 2022 the worst year for hospitals since the beginning of the pandemic.” It noted that from January to June, operating margins were down 102% from the same period in 2019.

“UCHealth at least for the moment is bucking that trend, but we have seen an erosion in our margins over the past year due to the increased labor cost and supply costs as well,” Unger said. “Inflation is certainly real, and we’re seeing it on all fronts.”

“The other thing that’s happened since 2019 — and I’ve been working for 25 years,” said Alan Qualls, CEO of Banner Health’s Northern Colorado division, is that “you could plan and budget pretty accurately every year. Ever since the pandemic, that’s turned everything upside down in terms of what volumes look like, your in-patient services or your emergency department, what acuity looks like. Everything is completely different now. It’s the weirdest thing because nothing seems to be predictable any more. Usually summertime is kind of a slower time for hospitals, but the last couple of summers our emergency departments have been absolutely crushed with volume.”

Qualls also cited the pressure “from pharmaceutical companies changing drug prices on us. We’ve seen an 11% increase overall in all supply-related, non-labor expenses. That’s fairly consistent with the overall economy but maybe a little bit higher.”

What sets current conditions apart from conditions during the pandemic, Vissers said, “is that this represents a long-term, significant financial challenge to nonprofit health systems that already have a small margin to work with. COVID was a public health crisis, and as challenging as it was, we’re used to dealing with health challenges. It was temporary. This is different. In this instance, we’ve had a dramatic increase in labor expenses — 16% more than a year prior for Boulder Community Health — plus significant increases in the cost of supplies. More than half our expense goes to providers and employees. When you expect an increase in reimbursements and then there’s all these take-backs, it just doesn’t work.”

Unger said UCHealth’s compensation to its staff has increased by about 21% systemwide over the past four years, “while our reimbursement is not keeping up with those inflationary trends.”

Some of those labor costs have been jaw-dropping.

“At one time during the pandemic, contract labor for one nurse was $200 an hour,” Qualls said. “ “It’s still pretty high, about 100 bucks an hour,” a variable figure based on whether the nurse works in an intensive-care unit, he said. “That’s come down, but you multiply that times hundreds of nurses.”

Why hire more expensive contract labor? About one-third of the nation’s registered nurses quit their jobs during the pandemic, Qualls said, adding that the average annual turnover rate for RNs with less than one year of tenure has soared to 24%.

“We’ve been trying everything we can to make sure we have adequate staffing to care for our patients” at Banner’s new hospital in Fort Collins along with McKee Medical Center in Loveland, North Colorado Medical Center in Greeley and its clinics throughout the region, he said. “We’ve been able to do that, but at a rather significant cost because we, like every other hospital in the United States, have had to turn to a lot of contract labor to fill our open positions — and that is very, very costly.

“A lot of effort being spent once you do recruit somebody is how to retain them,” he said. “It’s very costly to have turnover when you have to go out and recruit other people — and then you’re probably using contract labor to fill that gap.”

That torpedoes hospitals’ operating margins.

“Our margin is certainly lower than we’d like it to be. It’s been a really hard year from that perspective,” Qualls said. “We’ve still been able to buy the capital equipment we’ve needed this year, but again it’s just the way the world works.”

Cramer noted that “it’s no secret that workforce is the biggest challenge across all industries, but health care has probably been hit hardest with people getting out of the field or retiring or becoming travelers. We’ve definitely felt the strain on that, financially, coupled with the tremendous volume of patients we’re seeing” — not only from the local market, he said, but also from patients transferring into UCHealth hospitals from outside the state.

COVID also increased levels of stress throughout the industry, Unger said.

“We are building programs to emphasize both the mental and physical health of our employees,” he said, because “our patients have become more challenging. Families have become more challenging. I think that’s made health care a little less attractive. So we’re investing heavily in the well-being of our workforce to make sure they have resources that are necessary for their physical and mental well-being as well.”

Noted Qualls, “Our expenses are up for labor. Our expenses are up because of inflation. But yet our reimbursement is fixed and flat, so that’s creating a lot of margin pressure.”

Medicare payments for hospital inpatient services are to increase 4.3% in fiscal 2023 under a final rule the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services published this summer. And yet, the Colorado Hospital Association estimates that Boulder Community Health’s inpatient Medicare reimbursement will be 0.6% less in 2023. The reason is what Vissers called the “take-backs,” many of which involve the Affordable Care Act and Medicare’s “Disproportionate Share Hospital” adjustments.

“It goes down 0.3% for an ACA-mandated market-basket reduction, down 0.3% for a productivity adjustment, down 0.8% due to a change in our relative wage index and down 3.9% for an ACA-mandated reduction in funding for DSH uncompensated care to reflect the impact of insurance expansion under the ACA. The uncompensated-care pool is also distributed to hospitals based on each hospital’s proportion of uncompensated care for all DSH-eligible hospitals.”

He said more than 60% of BCH’s reimbursements are through Medicare at rates fixed by CMS, and “the remaining is from commercial insurance based on contracts that are often three years in duration. It does offset some of that loss, but it doesn’t come close.”

And meanwhile, he noted, “those commercial payers were making significant profits during COVID.”

Vissers said that creates “a huge gap, too large for any system to recover from in a given year.

“Many hospitals rely on cash savings in terms of investment return,” he said. “Like everyone, these investments have taken a significant hit. What results is a reduction in cash on hand to pay for operating expenses.”

The inevitable result? “What is happening and will continue to accelerate,” Vissers said, “are hospital closures, service-line reductions and layoffs. We heard that Parkview Pueblo has now been acquired by UCHealth since it was unable to continue on its own because of financial pressures.”

In a merger closer to home, Salt Lake City-based Intermountain Healthcare in April completed its acquisition of Colorado-based SCL Health, which includes Good Samaritan Medical Center in Lafayette.

“The mismatch between rising expenses and lower or lagging Medicare reimbursement creates challenges and pressures,” said Dawn Anuszkiewicz, Good Samaritan’s president. “It has our team looking for ways to reduce waste and looking for opportunities to make sure we’re able to finance the care folks need. But the merger with Intermountain gives us significant resources we can bring to bear — and allows us to be a forever organization caring for folks in Boulder County and across the Front Range.”

Qualls said Banner Health has “had to make other decisions very carefully around those parts of our business where we could reduce expenses so we could keep paying our bills.” He said the focus has been on “reducing discretionary spending if it’s something that can wait, something that we don’t need to do any more.”

Unger agreed. “We have to remain competitive in the market, but with that, it reduces margins and our ability to do programs the way we used to, so we’re looking at augmenting everything we do through technology if we can, but it seems like with increased regulations and legislation, that burden increases, which causes us to spend money in overhead, reporting, compliances, which sometimes takes away from the bedside focus, which is frustrating.”

Two Centura Health CEOs, Chad Hatfield at Longmont United Hospital and Isaac Sendros at Avista Adventist Hospital in Louisville, could not be reached for comment for this story.

Those hospital executives who did comment agreed that the picture certainly could be worse.

“We’re fortunate to be in a state like Colorado, where our hospital systems are healthier than many across the country,” Vissers said, “so we have a greater ability to weather the storm.”

In 2020, as a share of household income, Coloradans spent the second lowest amount in the United States on hospital care, just behind Utah — 18% less than the national average for health care per year, Anuszkiewicz said. That may be in part because residents of Colorado and Utah often are ranked as healthier than those in other states, but still it means “the opportunity to get high-quality care at a lower cost is easier here than elsewhere across the U.S.,” she said.

As with any crisis, the executives said, opportunities are created.

“At the end of the day, a health system is essentially highly skilled, compassionate teams working together, and we need to demonstrate that we need to care for them as well,” Vissers said. “Part of our challenge in labor is compounded because we’ve had so many leaving our workforce. We need to reimagine our workforce and how they work to make their work easier and help them work at the top of their license. We need to bring them more efficiency and remove some challenges that remove them from the bedside — either through a lower-cost employee who frees up a highly skilled nurse, making technology more a part of the team, or (identifying) things we can do remotely.”

To recruit and retain staff, Cramer said, UCHealth this year announced it would invest $50 million over the next five years to launch Ascend, an education and upskilling program offered in partnership with Guild Education and providing growth opportunities for employees while attracting new employees interested in pursuing a career in health care. “We’ll pay 100% of their education through that program,” he said, “and in return they commit to being with us for a year after they leave it.

“We’ve upped our education reimbursement up to $5,270,” Cramer said.

Unger said he is encouraged that of the 27,000 employees eligible for the program throughout the entire UCHealth system. “About half have at least taken the first step in filling out the initial enrollment form,” he said.

“For instance, if you’re in sterile processing and would like to become an RN, we will develop a career path. We will assist the employee in getting enrolled and getting into the right programs,” he said. “We provide mentoring and tutoring throughout the process to make sure they are going to be successful. Once they complete the program, we guarantee them a position.

“We are a service industry. We rely heavily on people. We are only as good as the people we have on board,” he said. “As a health system, we believe this is going to be our challenge for the next — maybe for the rest of my career. We’ve taken the bull by the horns, because if we’re going to be successful we’re really going to have to educate and train our own staff. We can’t be reliant on others to do so.”

Added Cramer, “I don’t think any of us can just hire our way out of this, so UCHealth has added new job codes internally” including six-week training to be a patient-care assistant, a new program for licensed practical nurses, behavioral-health technicians to help with patient management and intervention, patient technology technicians and mobility technicians.

“The point of that is that we can add helping hands and take some of the lower-level stuff off our nurses,” he said. “We need people working at top of scope.”

UCHealth is “doing our part to grow the provider workforce” as well, Cramer said, spending $287 million last year to support the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

However, said Banner Health’s Qualls, “one of the big issues from a nursing standpoint is that the nursing schools produce a pretty limited number of new nurses,” including only about 36 every semester at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley. “They also are having recruiting challenges recruiting instructors, so it’s kind of a vicious cycle,” he said. “They’re no different from any other university; they’re competing for a limited pool of qualified nursing instructors. They’d like to triple the number of slots they’ve got, but they’ve got issues on the supply side.”

Yet another challenge to keep health care workers employed is the cost of housing and other inflationary pressures.

“We are finding that it’s very challenging for new graduates in this market to afford to live in Northern Colorado,” Unger said. “The cost of living and especially housing is a detriment to recruiting employees to this market. We fare better than a lot of areas just because Colorado is such an attractive place to live, but many new grads, when they’re just starting their careers and trying to get their feet under them and they’re coming out with school debt, the cost of living is prohibitive. We used to be able to find lower-cost housing in outlying areas, and that is becoming harder to find. Housing prices in Wellington, Ault, Severance and Windsor have increased just as much as in the Greeley market, Fort Collins or Loveland. Housing affordability is certainly an issue for our workforce.”

Added Qualls, “Kevin and I were talking about that a few weeks ago. Even if you’ve got a travel nurse making big bucks, those folks look at our housing and say, ‘There’s no way I could stay here. It’s crazy.’ That even happens with physicians. All of us in the industry have a lot of open positions for physicians, but we get a lot of people who come here, look at it and say, ‘Oh my gosh, I’m not going to do that. I’m going to go to Texas. It’s cheaper to live there.’”

Offering higher pay and incentives could help ease that shock, he said, but “then you worry about when you do that, do you then not have equity with the other staff in that same given position. So you have to be real careful with that to keep everything fair.”

In Boulder County, Cramer noted, the median home value “is something like $750,000 right now, and that’s a significant purchase for someone in an entry-level role. I sit on the Longmont Economic Development Partnership, and we’re continuing to pressure communities to do incentives for builders to build more attainable housing and make it a fast track for builders to get permits. We need more inventory.”

Cramer is in favor of anything that will help hospitals retain their staffs.

“We’ve had about an 18% turnover rate, but the state as a whole is seeing 24% to 28% turnover in health care. If we can just retain a portion of that, we’re going to save ourselves a lot of headaches.

“We still have our pension and our health savings account benefits,” Cramer said. “It’s really important we keep our benefits strong. Re-engaging or re-recruiting internally will be an important strategy this year.”

At Good Samaritan, Anuszkiewicz said, “we’ve been successful at starting to recruit people back into our teams. We are training the next generation, and there are lots of opportunities and exposure to health care careers across our system.

“We’ve traditionally been one of the lowest-cost providers,” she said, and “that positioned us well, but challenges persist. We just have to make sure we are providing high quality at the right price and make sure we use our resources judiciously.”

“All these things take time,” Vissers said. “In the short term, every organization needs to be rethinking our capital investments and looking for non-labor savings.”

Meanwhile, he said, commercial payers — the insurance companies — ”are going to have to step up.” Increases of 3% or 4% in coverage “in the face of 12% increases in cost is no longer acceptable. Look at profit margins they’ve experienced. Some of that needs to be passed onto hospitals as well as the people they’re insuring. They’re legally constrained with limits to their profitability, but they’ve found ways around that. It would be healthier to divert some of that back to hospitals.

“Patients have had to defer a lot of their care over the past two years, which normally would be what you pay insurance for,” Vissers added, ”and yet that’s not led to a reduction in the cost of insurance for the people of Colorado.”

“We are going to have to lean on our commercial payers more,” Cramer said. “We cannot continue to just hold rates down.”

Legislative relief could help as well,” the executives say.

“Hospitals have to work with legislators to try and reduce the cost of health care.They just need to let the existing legislation play out. Our community leaders could help us seek some regulatory relief in the short term by avoiding piling on new regulations and let us focus on some of the legislation already put forward, to make sure it adds value and doesn’t cost more.”

Added Cramer, “We need a break from legislation” such as a mandatory nurse-to-patient ratio. “This is the best year going forward for our legislators to take a pause. We need to let them know this is a year to do nothing.”

With all the headwinds the industry is facing, Anuszkiewicz said, “If I had to bet, I’d bet on our teams. They live their vocations. The economic challenges make it tough, but we just have to make sure the next generation understands how fulfilling a health care profession can be.”

Added Vissers, “All these are the common conversations in my head between 2 and 3 a.m.”

Source: BizWest